100 years of the Chinese Communist Party

A sinologist’s view of a century of politics and culture in the world’s most populous country

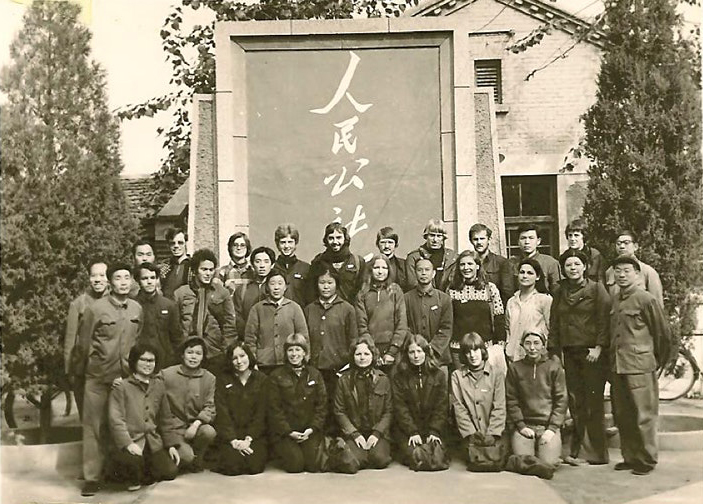

Frances Wood studied art, history and languages, including – very unusually for the times – Chinese. She first visited the country in 1971 and then returned to study at Peking University 1975-76. Like many in the British Council-funded group who shared this extraordinary experience, she went on to a professional role in which this early encounter with the language and culture was a crucial starting point. Frances became Curator of the Chinese collections at the British Library in 1977, remaining until she retired in 2013. She visited the country many times, travelling widely and meeting Chinese people in many walks of life.

Frances is still captivated by the evolution of this increasingly powerful country, with all its complexities and contradictions. Her books on China include ‘The Blue Guide to China’, ‘Did Marco Polo Go To China?’, ‘The Silk Road: 2000 years in the heart of Asia’, ‘The Forbidden City’, ‘The First Emperor’, ‘No Dogs and Not Many Chinese: Treaty Port life in China 1843-1943’ and an account of her year in the capital: ‘Hand Grenade Practice in Peking: my part in the Cultural Revolution’. (By the way, she says that Peking and Beijing are both acceptable versions of the name).

In this talk she covered in outline the birth of the Chinese Communist Party, how Mao came to the fore and stayed in control, the impacts of his leadership and then the remarkable series of changes since his death in 1976.

Recording and summary below

Here’s the recording of the talk. (Please don’t be put off by a few small random noises near the start. It settles down quickly into such a fascinating take on this huge topic.)

Summary of the talk

Studying Chinese half a century ago was, admits Frances Wood, a perverse choice. Its appeal? It was particularly difficult and as different as possible from languages she’d encountered so far. She still finds it endlessly fascinating: how the characters are constructed and how the terminology and slogans relate to the ancient culture, despite the deliberate break with tradition in 1921 when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was founded. Since the death of Mao Zedong (1893-1976), historic Chinese features have even been resurrected, while so much that originated beyond their vast nation has been embraced. Communism always had uniquely Chinese characteristics and now it co-exists with a most energetic form of capitalism.

In the mid-1970s China was yet to enter its era of super-charged industrialisation and urbanisation. The majority of the people still led simple, rural lives with few possessions in their crowded traditional houses. They travelled by bicycle, in army trucks or on buses.

Before being installed with her patient Chinese room-mate at the university, Frances spent a night in a hotel in the heart of the capital. She was woken that first morning by bleating noises and peered out to see a flock of sheep being driven up the street. During the winter, she noted gatherings on street corners as locals in padded jackets soaked up warm sunshine. With skyscrapers and air pollution now obscuring the sun, such scenes are a thing of the past.

The British students were there to learn not only the language but also Chinese history. They had to rise early each Saturday for two hours on Mao’s thought – ideas that did not adhere strictly to Marxist-Leninism. They heard of Mao’s ‘10 great line struggles’: how he rose to the top of the Chinese Communist Party and stayed there for so long. Mao was a junior library assistant at Peking University in 1921 when he and a small group held the first meeting. All the other founders, apart from one, died or split with Mao in the following decades of struggle.

Soviet Russia was never a straight forward ally of the Chinese Communists. In Stalin’s view, as a pre-industrial country without a proletariat as such, the Communists should join with Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalist Party, become industrial, and work towards a proper Communist Revolution. Mao was not concerned that the majority of Chinese were peasants.

He was, though, motivated to redress the cruel blow suffered by China after World War 1, in which the Chinese had served the Allied cause. The Versailles Treaty awarded Chinese territory to Japan, and the Japanese encroached further. The USA and Soviet Russia supported Chiang Kai-Shek to resist the Japanese. Yet Chiang spent more of his time and resources against Communists than against the Japanese. In 1927, workers had managed to seize Peking. When Chiang’s army arrived in the north, Communists were massacred. Mao managed to escape and built more of a following amongst the peasants. Surrounded by Chiang’s forces, he and supporters embarked on the Long March to set up a new base. As support for him gradually grew in the rural areas, he gathered enough forces to oust the Japanese and then consolidated his position.

By 1956 Mao was confident enough to call for new ideas from the people: ‘Let 100 flowers blossom’, only to retreat from this when his grip on power looked less secure. Instead he launched ‘The Great Leap Forward’ in 1958, insisting that industry should be spread around the countryside. The Chinese should ‘walk on two legs’, not just rely on heavy industry like Stalin. An infamous famine ensued. The Cultural Revolution 1966-1976 was, in Frances’s words, ‘a last gasp’ of trying to keep alive the idea of revolution, to demonstrate zeal for communist ideals, engage young people and keep criticising anyone insufficiently revolutionary, so avoiding a descent into corruption and comfort.

With Mao still at the helm, retaining his staunch support for the rural population, intellectuals were labelled ‘ivory towerists’. So Frances and her fellow visiting students also had to learn from workers in the fields of the ‘eternally green’ people’s commune, within sight of the New Summer Palace. They picked spring onions, planted rice and bundled Chinese cabbages with rice straw. Cabbage was a staple of the monotonous and minimal winter diet. There was great excitement in March when celery was added to the narrow repertoire.

But by 1976, people were fed up with the repetitive political movements, orders to attend political meetings, and the lack of consumer goods. With Mao’s death, the time was ripe for a new direction. The incoming leader, Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997), had been a star of the military campaign to take southern China in his youth. Amazingly he survived the intervening years, despite being less purist and more pragmatic than Mao. He encouraged dramatic and rapid transformation in the operation of the economy and in the way of life.

Xi Jinping (born 1953) has been Paramount Leader since 2012. The latest slogan, ‘China Dream’, has simply been pinched from America. Being a rich and powerful nation is the main aim, retaining a strong sense of identity while engaging more with the outside world. The scale of cities still strikes Frances as extraordinary and rather baffling, and the environmental damage done within the country and globally is huge. But millions have been raised out of poverty, without creating a population explosion.

Yet for the CCP to maintain itself for the next 100 years, it needs not just to be tough and invest in infrastructure to maximise reach for resources and routes to markets (‘the new silk roads’); it needs to have a dream with a different kind of substance. Could it be a fearless leader on climate change? Judging by the vast extent of solar and wind farms, there is surely potential to work at pace and at scale across many other elements of mitigation and adaptation.

The Chinese are writing a new history of the CCP. Mao will feature less prominently than when Frances first went to China in 1971. Uncomfortable episodes of the twentieth century were omitted from the 1970s university courses, and the Chinese still have not resolved how to deal with events of the cultural revolution. Another 100 years may have to pass before they can confront and recount what really happened.

Rachael Unsworth, Events Secretary

Other events you might be interested in...

Explore more

Grants

The Society makes grants both to individuals and to organisations in support of cultural and scientific activities which increase innovation, outreach and diversity in Leeds and its immediate area. It also supports local museums and galleries and publications relating to the city.

Events

Since 1819, the Phil & Lit has been inviting the people of Leeds to hear from knowledgeable and entertaining speakers. Many are leaders in their field of science, arts or current affairs. We also hold an annual Science Fair and organise occasional visits.